Prologue to the book The Deutsch Affair

Comment: This book exposes a veritable state crime in West-Germany but also laid a track to Saxony, where many art treasures have been consigned. Amongst others things the Hatvany-Collection. The book is a kind of guide to finding them.

It was the painter Georg Chaimowicz who had first pointed out the case of Hans Deutsch to me. His words still ring in my ears, even though he has long left the world of the living: “Those who profited from the plundering and murdering of Jews will do anything to cover it up.” This applies to the story recounted here. It’s an open-ended story based on more than 20 years of research. I am a journalist who has been involved in politically charged issues in Europe, Central America and the Middle East. But it takes more than professional interest to tackle such a mammoth project; personal motivation is needed as well.

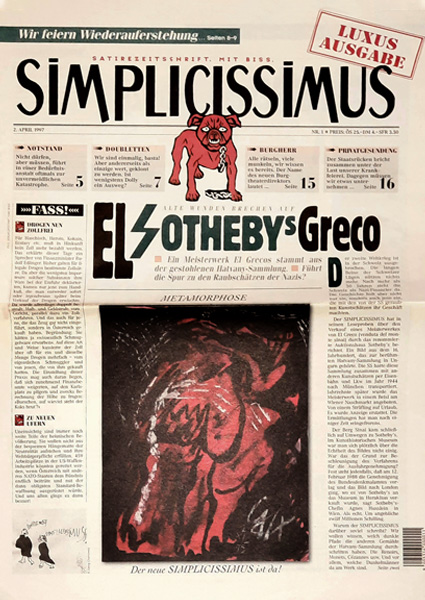

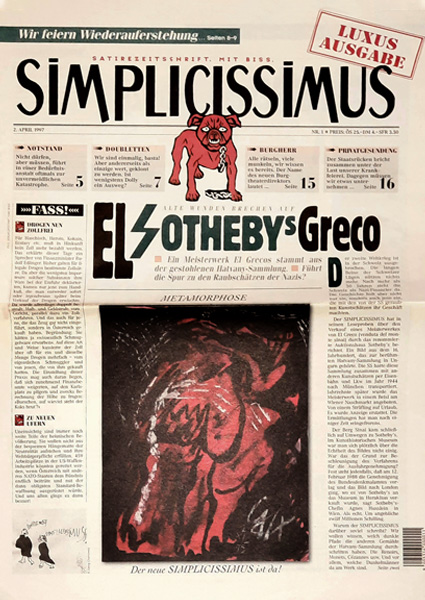

As a publisher, acting editor and chief partner, I played a major part in reviving the legendary satirical publication “Simplicissimus” in 1997, and giving it a new lease of life. I should have been warned that the national-conservative atmosphere of Vienna’s new elite was no supportive environment for that.

That could already be observed 10 years earlier, when Thomas Bernhard directed a play titled “Heldenplatz” in Vienna’s Burgtheater. A cultural struggle of inconceivable extent ensued, with foul disputes and hate-mongering in the Kronen-Zeitung. It was global news when a man actually drove his tractor to the theatre to deposit a load of manure there. The play was considered a treason because Bernhard’s hero contemplated that one had to be either a National Socialist or a Catholic to be tolerated in Austria. Bernhard wrote that the country had gone to seed and was mouldering. Behind the animosity against him, the author smelled the thieves and murderers of the Third Reich; having feasted on ample bounty, they now played high society. The theatre piece was incongruent with the state-promoted lie that displayed Austria as the “first victim of National Socialist tyranny”. That lie also served as the basis of the lives of many of the upper crust.

It was in this climate that the new “Simplicissimus”, a satirical presentation of such psychological contaminations, was launched. The general public reacted very positively to the initial tests (reader surveys involving half a million copies distributed free of charge); the publication should have been a sure-fire success. But unexpected problems arose at the time of the third regular edition: a bank suddenly refused to disburse a fully secured credit line, and also failed to release the collateral. There were conspicuously frequent delivery mistakes as large batches were misrouted to small towns, whereas cities received just a few copies. Such accidents were frequent enough to indicate a strategic blindness by the distribution company. Influential people attempted to intimidate the publisher; the director of Vienna’s Art History Museum intervened to prevent cooperation between a large daily paper and the “gutter paper”. In order to escape this phalanx of obstruction, the newspaper with a red bulldog as a mascot finally moved to Berlin. Despite all efforts, “Simplicissimus” came to an end in 1999.

But what really made the tempers flare? As my research clearly shows, it was the lead story of the first edition: an article about “Veduta del Monte Sinai” by El Greco, an inconspicuous painting considered to have been vanished. Painted on two boards, it is merely 41×47.5 centimetres small. The story was brought to me by Georg Chaimowicz in 1995.

A small oddity in the world of art: A painting that had been deemed lost emerged in Vienna’s Naschmarkt in 1980, just to disappear again. During the German occupation in 1944, it had been stolen by the SS from baron Ferenc Hatvany, a Hungarian art collector.

All right, it’s at least a story worth investigating, I thought back then. Little did I know that embarking on this research was one of the most momentous decisions of my life. This mundane crime story was to balloon into an international scandal.

The title page of the first edition in 1997 heralded: “El Sotheby’s El Greco – a masterpiece by El Greco came from the stolen Hatvany collection. Does the trail lead to the stolen bounty of the Nazis?” The article ended as follows: “We want to know what dark paths the other paintings of the Hatvany collection have travelled. The Renoirs, Monets, Cézannes etc. And most of all, we want to know what shady characters are at play.” The perpetrators and the beneficiaries must have interpreted that as a serious threat. They must have assumed that I, as a former investigative journalist, took the matter seriously. And that turned out to be true once their actions against Simplicissimus had revealed the dimensions hidden behind the allegedly minor case of “Sinai”. This book confirms those assumptions.

The title page of the first edition in 1997 heralded: “El Sotheby’s El Greco – a masterpiece by El Greco came from the stolen Hatvany collection. Does the trail lead to the stolen bounty of the Nazis?” The article ended as follows: “We want to know what dark paths the other paintings of the Hatvany collection have travelled. The Renoirs, Monets, Cézannes etc. And most of all, we want to know what shady characters are at play.” The perpetrators and the beneficiaries must have interpreted that as a serious threat. They must have assumed that I, as a former investigative journalist, took the matter seriously. And that turned out to be true once their actions against Simplicissimus had revealed the dimensions hidden behind the allegedly minor case of “Sinai”. This book confirms those assumptions.

Restitution lawyer Prof. h.c. Dr. Hans Deutsch holds the key to a mystery that still claims victims today. Hatvany’s heirs had charged him with enforcing their restitution claims. He had worked out a settlement in the amount of 35 million German marks, half of which had already been paid. But then he was unexpectedly arrested for fraud and kept in pre-trial detention for 18 months. His trial was protracted for years. Although finally acquitted, he remained discredited, and doubt is still cast on his findings. Also, false statements claim that the Hatvany collection had not been stolen by the Nazis but by the Soviets.

The title page of the first edition in 1997 heralded: “El Sotheby’s El Greco – a masterpiece by El Greco came from the stolen Hatvany collection. Does the trail lead to the stolen bounty of the Nazis?” The article ended as follows: “We want to know what dark paths the other paintings of the Hatvany collection have travelled. The Renoirs, Monets, Cézannes etc. And most of all, we want to know what shady characters are at play.” The perpetrators and the beneficiaries must have interpreted that as a serious threat. They must have assumed that I, as a former investigative journalist, took the matter seriously. And that turned out to be true once their actions against Simplicissimus had revealed the dimensions hidden behind the allegedly minor case of “Sinai”. This book confirms those assumptions.

Restitution lawyer Prof. h.c. Dr. Hans Deutsch holds the key to a mystery that still claims victims today. Hatvany’s heirs had charged him with enforcing their restitution claims. He had worked out a settlement in the amount of 35 million German marks, half of which had already been paid. But then he was unexpectedly arrested for fraud and kept in pre-trial detention for 18 months. His trial was protracted for years. Although finally acquitted, he remained discredited, and doubt is still cast on his findings. Also, false statements claim that the Hatvany collection had not been stolen by the Nazis but by the Soviets.

My research of this huge puzzle is based on thousands of documents from nine countries and 20 archives, as well as on numerous interviews with the persons involved. Especially with Dr. Joram Deutsch, who never tires of fighting the Nazi legends about his father so that he can be publicly rehabilitated. Despite the obstacles repeatedly raised before my research, despite existential threats and suddenly sealed information sources, the evidence is now overwhelming: the case of Hans Deutsch / Hatvany hides a tangle of connections leading to the highest echelons of German ministries where the strings were drawn by former Nazis pursuing their own totalitarian agenda. This National Socialist circle orchestrated what is arguably the most successful disinformation campaign in Germany’s post-war history; in fact, it is still at work today. This book intends to reveal the complex connections and shed light on the scary events, so that the truth can be established.